Vascular anomalies

1.1. Infantile haemangioma

Infantile haemangiomas are the most common benign tumour in infancy, with an incidence rate of 5–10% in the paediatric population. These tumours are either not present when the child is born or only a light pink or white-coloured mark can be seen. These tumours have a rapid growth rate in the first three months of life. Then, when child is approximately one year old, the tumour starts to improve without the need for treatment and regress or heal spontaneously. Sometimes there are more they can be multiple.

They may appear in any part of the body, but they more commonly affect the skin on the head and neck (60%).

Infantile haemangiomas can be superficial (bright red and not particularly raised), mixed (bright red and raised), or deep (darker colour but bulging).

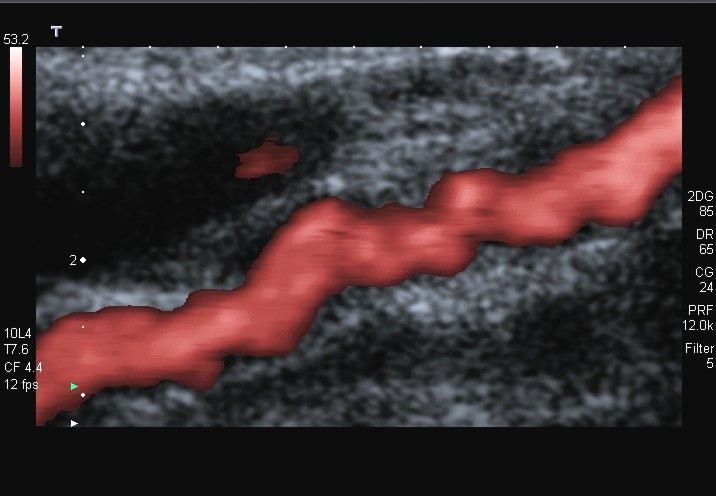

The diagnosis of haemangiomas is generally performed clinically because there is practically no other injury with such a characteristic clinical course: not present at birth, grows rapidly and regresses spontaneously just one year after it appears. Only deep haemangiomas can generate some doubts in the diagnosis, as they can be confused with a venous malformation or a lipoma. In these cases, it is usually enough to perform a Doppler ultrasound (a technique to visualize the blood flow in body structures using an ultrasound machine) in order to clear up the diagnosis.

Most infantile haemangiomas (90%) do not require treatment because they regress spontaneously. Depending on the size or location, sometimes we cannot “wait” for spontaneous resolution and they will require treatment with propranolol.

Some haemangiomas that take up a whole side of the face or the lower part of the back may be associated with another internal abnormality. These are known as PHACEs or LUMBAR syndrome, respectively. This does not occur with haemangiomas that are round or focal, i.e. that have a circumference-like shape as if they were drawn with a compass.

1.1.1. PHACEs syndrome

As mentioned in the previous section, this syndrome is related to segmental haemangiomas of the face. It is important to know that this is a very rare syndrome and that a child born with a segmental haemangioma of the face will not always have PHACEs syndrome. PHACEs is an acronym that describes all the abnormalities associated with this syndrome in a single word:

- P: Posterior fossa abnormalities

- H: (Segmental) haemangioma

- A: Arterial anomalies

- C: Coarctation of the aorta and other cardiac abnormalities

- E: Eye anomalies

- S: Sternal raphe

Haemangiomas and vascular anomalies are the most common abnormalities and can be found in up 91% of the cases described in this syndrome. Cardiac anomalies and coarctation of the aorta are the second most common abnormality, appearing in 45% of cases.

The accumulated risk that a child with segmental haemangioma of the face has of developing PHACEs syndrome is between 20% and 31%. The possibilities of a patient to have PHACEs syndrome depend on the anomalies accompanying the haemangioma. It is more likely for the patient to have PHACEs if it is accompanied by abnormalities of the cerebral arteries than if the haemangioma is only accompanied by ocular abnormalities. We also know that the bigger the facial haemangioma, the more possibilities of developing PHACEs.

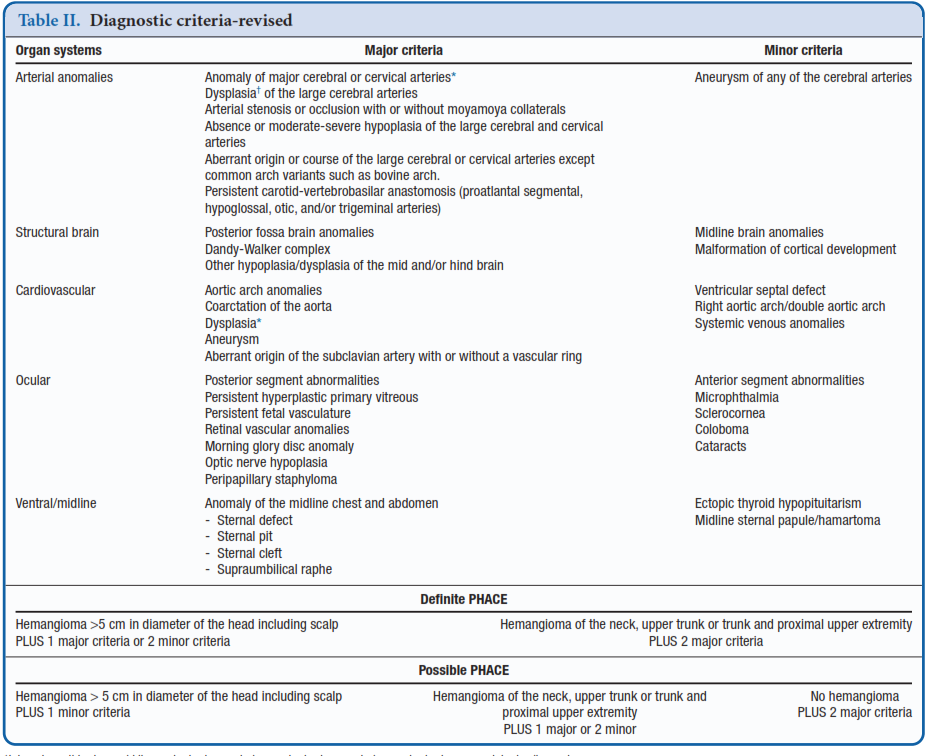

Diagnostic criteria for PHACEs syndrome

Following these criteria, we are able to say that a child has PHACEs, as long as:

- He/she has a segmental haemangioma of >5 cm in the head or neck region, plus one major criteria or two minor criteria.

- He/she has a segmental haemangioma of the neck, upper chest and upper limb plus two major criteria.

Therefore, we need to investigate potential PHACEs syndrome in all patients with:

- Large segmental haemangiomas of the face of >5 cm.

- Segmental haemangiomas of the scalp.

- Segmental haemangiomas of the trunk plus one other major criteria.

- Patients without segmental haemangioma but with two major criteria.

The symptoms of patients with PHACEs syndrome will depend on their cardiac anomalies. The most common anomaly is cerebral artery anomaly. These anomalies may not cause any symptoms or they may cause a deficit in the blood supply to the brain. The seriousness of cerebral artery anomalies can be assessed in a resonance angiography scan. Some anomalies are very mild and it will not be necessary to follow them up at all and others must be checked regularly or if other symptoms such a headache or signs of a lack of blood supply to the brain occur.

Patients with PHACEs syndrome may have a growth hormone deficit and this can be suspected by monitoring the child’s growth.

Depending on the location of the haemangioma, patients may have an issue with pronouncing words and children will need the help of a speech therapist.

The treatment is the same as the one given in infantile haemangioma and the complications associated with this syndrome will also be treated individually. That is to say, propranolol will be given for the haemangioma, and, if the patient needs surgery for the coarctation of the aorta, posterior fossa anomalies, ocular abnormalities, etc. this will be carried out. Logically, the most serious anomalies will be prioritised and then we will continue down the scale until the last anomaly is resolved. The treatment and follow-up vary enormously in each case and the family and the doctor must reach an agreement.

1.1.2. LUMBAR syndrome

This is also a very rare syndrome, but it needs to be taken into account when a patient with a segmental haemangioma in the lumbar/sacral or pelvic region comes in. LUMBAR is an acronym that describes the potential anomalies associated with this syndrome:

- L: Lower body haemangioma

- U: Urogenital anomalies and ulceration

- M: Myelopathy

- B: Bone deformities

- A: Anorectal and arterial anomalies

- R: Renal anomalies

Myelopathy is the most common abnormality in LUMBAR syndrome and can be seen in up to 87% of cases. The symptoms of myelopathy can be a lack of control of the urethral sphincter, or pins and needles and pain such as sciatica in the limbs.

Patients with haemangiomas of >2.5 cm in the vertebral column with lumbar or sacral involvement will be screened for the presence of LUMBAR. These do not include haemangiomas that are exclusively located in the perineal or coccyx region. To screen for LUMBAR syndrome, a lumbar MRI scan must be performed, as an ultrasound is not enough for diagnosis.

The treatment will be the same as it is for PHACEs but it will be focused on the abnormalities associated with this syndrome.