Kabuki syndrome

1. Growth

Growth in humans is determined by multiple factors. Adequate nutrition is essential, but it is also crucial that there are no bone problems, such as spinal deviations or deformities in the limb bones, for individuals to reach their genetic height potential. Additionally, growth is influenced by hormones, primarily two hormones: growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor (IGF).

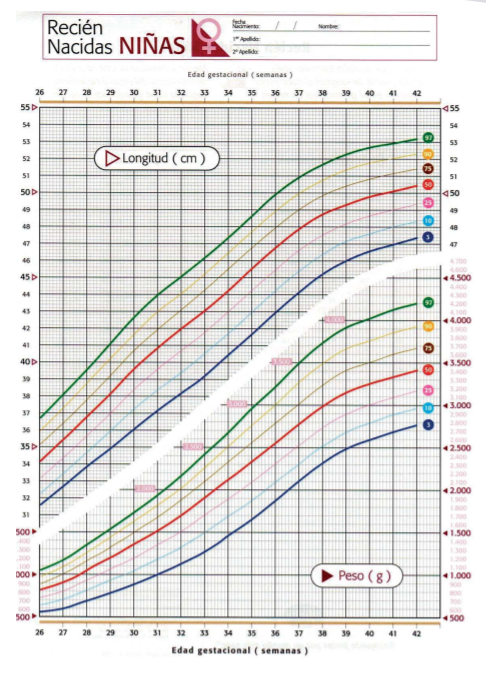

Most newborns with this condition are born at term (around 9 months of gestation) with normal weight and height. During the first few months of life and up to 4-5 years (or even later), it is not uncommon for children to present with weight and height below the normal range.

Infants with Kabuki Syndrom often experience growth delays for various reasons, including hypotonia, feeding difficulties, gastroesophageal reflux, and vomiting.

Without specific treatment, postnatal growth deficiency becomes more evident by 12 months. The absence of the typical growth spurt during puberty exacerbates short stature.

The treatment for these patients should focus on maintaining adequate nutritional intake, sometimes requiring the placement of a nasogastric tube or gastrostomy.

Short stature, even in the absence of growth hormone deficiency, has responded to growth hormone therapy without exacerbating disproportion. In a study conducted by Schott et al. in 2016, the average height in adults with SK without growth hormone was between -2.99 SD (standard deviations) and -1.08 SD in men, and between -5.57 and -1.47 SD in women. After one year of growth hormone treatment, the average height standard deviation score improved from 2.40 to -1.69. Those who started growth hormone therapy at an earlier age experienced the greatest benefit in terms of catch-up growth.

After one year of growth hormone therapy, body proportions were not significantly affected.

In any case, its use should be evaluated by an endocrinology specialist on an individual basis for each case.