Epidermolysis bullosa

5. Diagnosis of EB

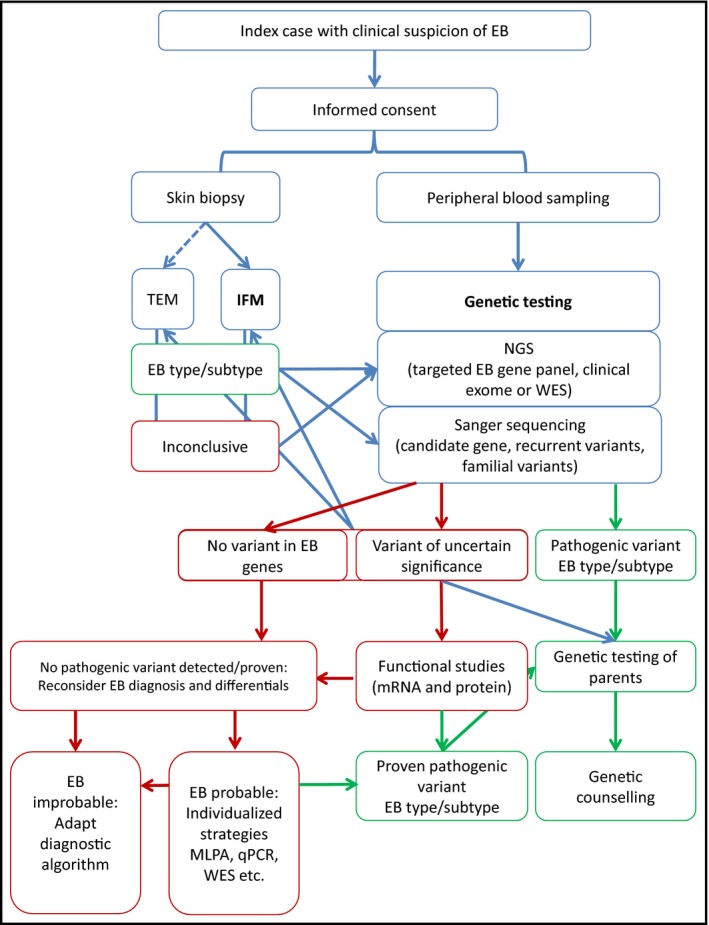

Accurate disease diagnosis is pivotal for ensuring optimal patient care and offering the most effective therapeutic options. In the context of epidermolysis bullosa, a condition typically manifesting at birth, initial clinical diagnosis by medical professionals often precedes laboratory-based diagnostic assessments. Clinical diagnosis hinges on symptom evaluation by healthcare experts, leveraging their understanding of the disease. Subsequently, laboratory tests, including biopsies or genetic analyses, are conducted to confirm the clinical diagnosis (Figure 7).

Diagnostic examinations play a critical role in identifying the specific type and subtype of EB, as they unveil the precise genetic (DNA) and protein-level triggers. For individuals struggling with EB and their families, obtaining this information holds significance for the following reasons:

- Precise genetic counselling

- Prediction of disease progression and severity

- Informed decision-making

- Comprehensive and suitable care

- Access to prenatal and preimplantation diagnoses

- Capability to access specialised medical attention

- Provision of wound care materials at no cost (as per the interterritorial agreement in Spain)

- Opportunity to engage in clinical trials

Diagnostic tests

The main tests used for EB diagnosis are (Figure 8):

- Skin biopsy analysis: Several techniques are employed to detect changes in the location, structure, or quantity of the affected protein due to the genetic mutation.

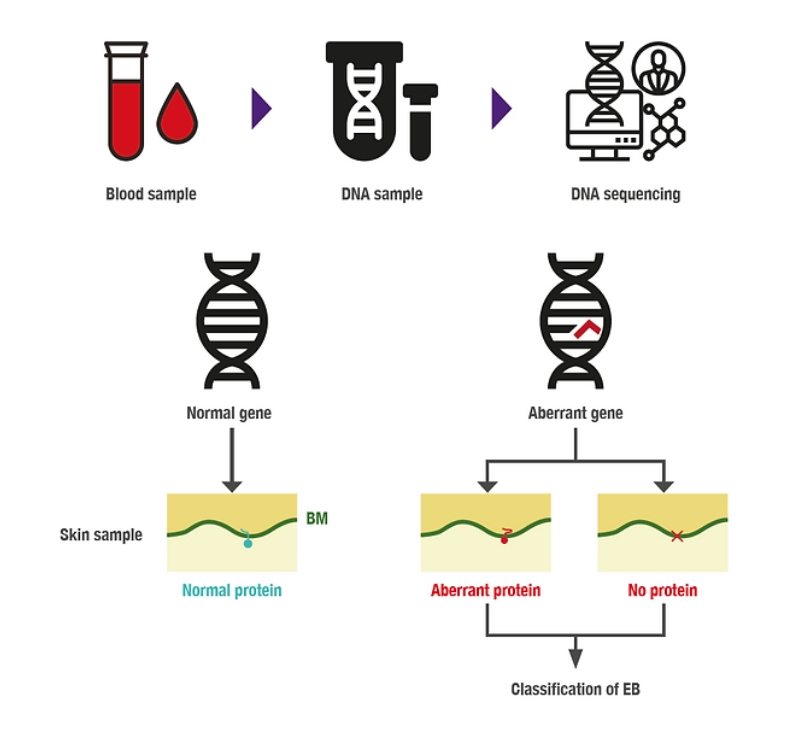

- Genetic analysis: To identify specific variants or mutations causing the disease. A blood sample from the affected individual is required, from which the DNA to be studied will be extracted.

Skin biopsy

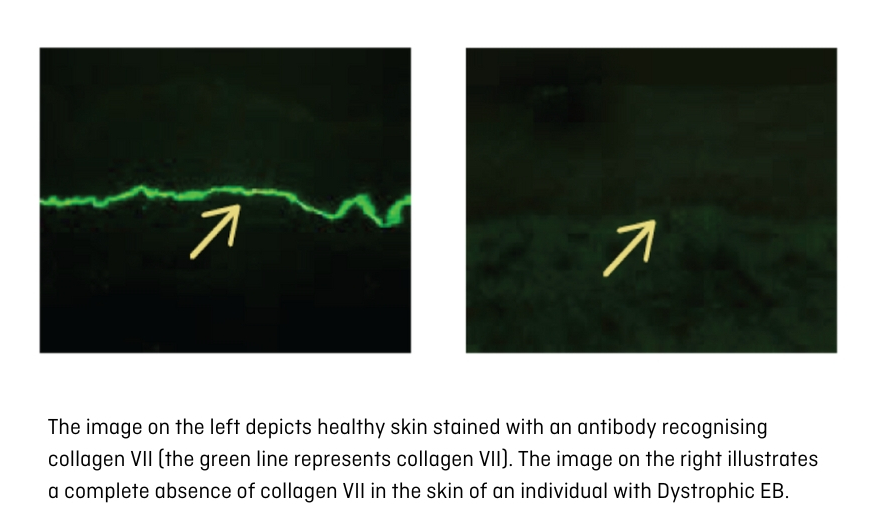

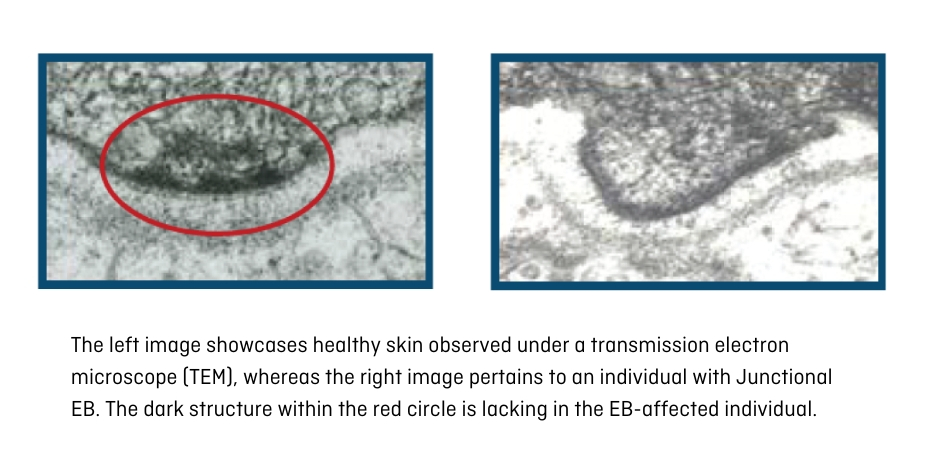

These diagnostic procedures can be conducted using two distinct techniques: immunofluorescence mapping (IFM) or transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In both scenarios, a skin sample from the person with EB is essential. This involves inducing a blister on the skin and extracting a section of this skin for analysis to scrutinise the plane in which the blister develops and the proteins or structures that are impacted. Collectively, this provides preliminary insights for diagnosing EB, a diagnosis that can be subsequently confirmed through genetic and clinical assessments.

Immunofluorescence mapping (IFM) is the initially recommended diagnostic measure, given its fastness in offering insights into the individual's condition within a few days. In the case of EB, IFM aids in identifying the specific type. IFM meticulously examines skin proteins, with the use of especific laboratory reagents enabling the detection of EB-associated proteins. When juxtaposed with a sample of healthy skin, this technique reveals the deficiency or reduction of said protein quantities (Figure 9).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is no longer routinely employed for EB diagnosis, but it can prove highly valuable for confirming or resolving intricate cases. This method delves into the skin's internal structure beyond the scope of conventional microscopes, offering magnification up to 10 million times (Figure 10).

Genetic analysis

To achieve a genetic diagnosis, we need a blood sample from the individual with EB. In many cases, samples from the parents are also necessary, as the complementary genetic study helps to corroborate the mutation responsible for the disease, as well as determine the inheritance pattern.

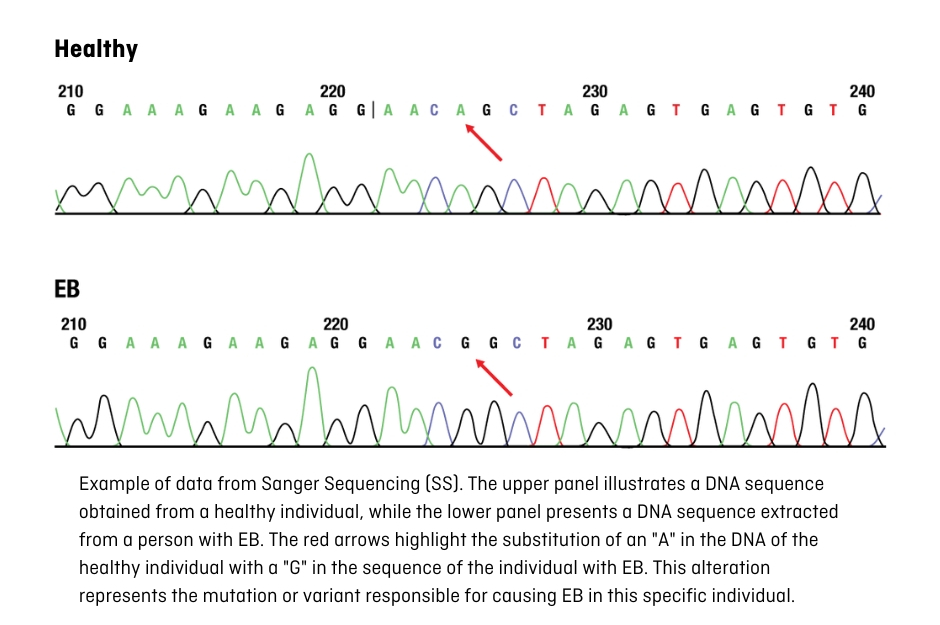

DNA includes all the genetic information within our bodies. It comprises around 25,000 genes, each characterised by its distinct sequence that yields a protein with a specific function. The DNA sequence contains four letters (A, T, G, C) reiterated to construct a singular text unique to each gene. When variations occur in this text, the resultant implications at the protein level can lead to disease (Figure 11).

These variations or mutations can be identified using the Sanger sequencing technique (SS), which focuses on a specific gene, or through massive sequencing (Next Generation Sequencing or NGS), which is capable of analysing many genes at the same time. The latter has contributed to expedited result acquisition; however, skilful interpretation of the findings needs the involvement of scientific, bioinformatic, and medical personnel (geneticists).

Recommendations

If the clinical characteristics of the individual and/or family history suggest an EB diagnosis, we must carry out diagnostic tests with the informed consent of the patient, their parents, or legal guardians.

- For starters, a regular evaluation should be done to rule out other hereditary or acquired skin conditions.

- Ideally, we must perform genetic analysis and a skin biopsy to fully understand EB from a genetic to a protein level. These methods give us additional information to predict how the disease might progress.

- When planning the EB laboratory diagnosis, we must take into account factors like benefits to the person with EB and their family, the availability of different methods, and national and economic regulations. Prioritising certain strategies can speed up the diagnosis process and save resources, but it calls for the expertise of the scientific and medical staff. Consider the following strategies for EB diagnosis:

- For babies, analysing a skin sample should be the first diagnostic step since it provides quick results. Simultaneously, genetic tests should always be done as early as possible.

- A genetic diagnosis can be crucial for confirming the diagnosis in cases with typical clinical characteristics.

- In complex cases or those with unique clinical features massive sequencing or NGS is recommended, as it covers more genes and leads to a quicker diagnosis.

- If the variants (or mutations) causing the disease are found in a person with EB, their parents should also be evaluated to determine the inheritance pattern. It might also be a good idea to have other family members tested to enable genetic counselling.

- If the variants causing EB are not identified, the steps to reach a diagnosis should be re-evaluated and additional laboratory tests should be considered.

I have received the diagnosis. What's next?

Once you have the results of the diagnostic tests along with the clinical observations, it is key to convey this information to the person with EB or their family. The laboratory or hospital should avoid directly providing diagnostic reports to the patient or family to prevent misinterpretations, as these reports are often presented in scientific and medical terms. Specialised medical personnel or a genetic counselling session (with geneticists) should be who communicate the results to the family or patient. Through genetic counselling and medical consultation, questions can be addressed, such as:

- What is EB?

- Family inheritance pattern

- Explanation of the diagnostic test results

- Prediction of the severity of the disease

- Family planning options

- Prenatal/preimplantation diagnostic options