Àngels Ponce: «It never ceases to amaze me how children actually see illness and disability as natural things»

S4R: It is difficult to know that a child is having a hard time if he/she does not express it. Often, the siblings of sick children prefer not to bother their parents with their problems if they perceive that the situation at home is complicated. What signals should set off alarms?

AP: First, I would like to emphasize that children go through different stages in their development, and the experience of their sibling's disability does too. This means that they will experience different emotions that can be intense, but we should not be alarmed by this.

In general, behaviors that move away from the usual behavior of their peer group (children of the same age) could be considered as warning signs. In the case of siblings of children with disabilities, I will highlight two things that I have observed:

1) When children are “super-responsible”: good grades, exaggerated predisposition to collaborate with domestic tasks or in the care of disabled siblings… but the same time suffer from a certain social isolation: they prefer being at home than with their classmates, they refuse to go to camps or do extracurricular activities. From my point of view, these children prefer to satisfy their parents than themselves, and this greatly puts their development at risk.

2) When a child manifests a deep sadness or apathy, which continuously isolates him/her from his/her environment.

It is important to bear in mind that "we should not blame disability for everything" and that there are other factors that can affect children (and families); therefore, it is important to explore the entire situation and the environment when a certain behavior occurs.

AP: If they "show" their discomfort, if they express it, this is a good sign! By this I mean that this allows us to recognize how the child feels, to pay attention to him and give him/her what he/she needs. Regarding jealousy, parents should see it not as something that we have to avoid or alleviate, but as something that arises naturally among all siblings (in the end, it is normal for them to compete for monopolizing the attention of parents). When there is jealousy among siblings, it is us, adults, who feel "guilty" for not being able to distribute our time and attention equally, and if one of our children has special needs things get complicated.

We must also remember that the key is not to distribute our attention equally but to give each one what he/she needs, because every kid is different and has his/her own character and personality. If we aspire to be equitable we will feel more frustrated because it is really difficult.

On the other hand, it is also important to remember that what children need is our full attention (without interference, interruptions or distractions). This is how we give them quality time.

Thus, if we bear this in mind, it will be easier to pass it on to the children, to love each one for who they are, without comparing them and above all, to be able to dedicate from time to time an exclusive attention to each one without feeling guilty for it (and without controlling the time.

S4R: Is any age appropriate to explain the illness of a sibling to a child?

AP: Yes. It is necessary to deliver this information in a direct and transparent way, because it affects the children’s environment, family dynamics and naturally, it touches someone they love deeply. Children need to understand. But they also need information suitable for their age: they must be able to understand it. Children do not need the same explanations as adults and this is crucial. I always say: specific questions need concrete answers. It is not necessary to give them a talk about a syndrome or disease, but to respond to what the child is worried about at that very moment: “Will he/she be able to walk one day?”; “Can this happen to me?” The child will ask once, twice, twenty times ... as many times as necessary, while all the pieces fit together. It is not that the child does not understand the situation at once: that is how he/she builds his/her understanding of the world: asking. If we do not give them the answers them need, they will probably build an explanation in their mind that does not fit reality (and can even cause fear). As they grow, we will provide them with answers that are age- appropriate.

S4R: Broadly speaking, what kinds of support do siblings of a child with a rare, disabling or chronic illness need?

- AP: I would distinguish between children who have a sibling with a disability and those who have siblings that have suffered an unexpected health problem. But in general, children need clear information about what’s going on. The best support is to be close to them, to accompany them and to know first-hand what they need at all times (because their emotions will change as they grow). Therefore, communication is key.

It is also vital to normalize their emotions, no matter how negative they may seem: children have the right to feel jealous, to be angry, to feel shame ...

Being in touch with other siblings helps them feel that they are not the only ones living in this situation and therefore, it is also a great support for them.

S4R: Do you think that, in the long run, such an experience can benefit or help these children develop positive qualities or skills that other children who have not lived this situation would not develop so easily?

AP: In the case of investigations that have been conducted with siblings of children with disabilities, they show that this condition does not necessarily have a negative impact on the development of the sibling. But it is very significant that, when they are young or adults, studies have found special skills that they point out when asked about their experience, such as: greater self-confidence, empathy, sense of social justice, solidarity, willingness to help ... Many of these brothers and sisters choose professions where they can help or assist other people: teachers, physiotherapists, doctors, speech therapists ... or work in centers and services that serve people with disabilities. This does not happen just by chance.

S4R: How would you recommend working on this topic in schools?

AP: We need to be natural, especially when working with children. From my experience, it is really useful to address the issue of disability by explaining diversity: in our world diversity is a fundamental characteristic (trees are different, fish are different ...), so, logically, people are different. But deep down, we are all equal in terms of our most fundamental needs, and although apparently we are different, we are all capable. I use this strategy even when there is a special sibling in the classroom, inviting them to explain their experience (if they feel like it). I am amazed at the naturalness with which children see this reality (perhaps it is adults who have more prejudices about it).

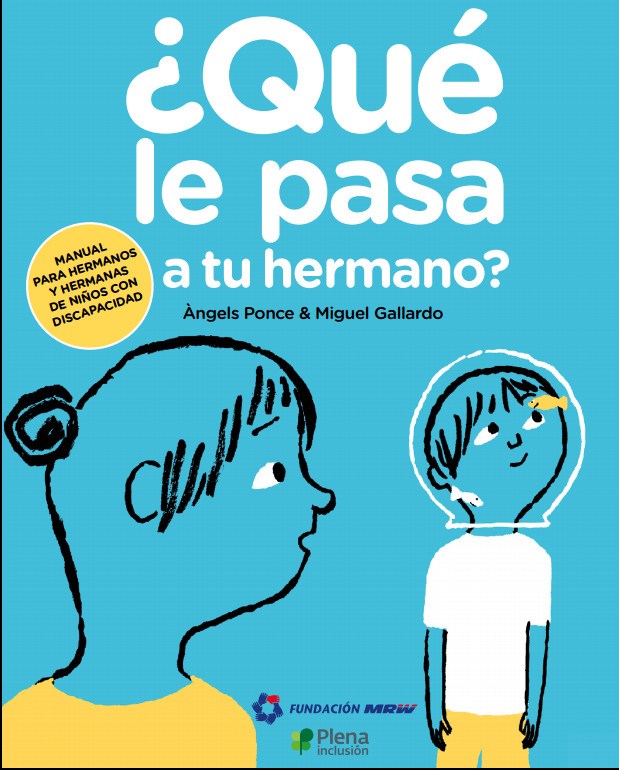

S4R: Who is your book “What happens to your brother?” for?

AP: It is aimed at brothers and sisters of children with disabilities, but it is also book addressed to their parents, so that they can talk about emotions together. Thus, children can express what they feel and parents are able to know where they are and to have their backs. It is also a book that can be used at school, it is very practical.

Àngels Ponce will participate as a speaker in the event "Taking care of the siblings of children with rare diseases" that will take place on October 28th at Sant Joan de Déu Children’s Hospital in Barcelona.