Osteogenesis imperfecta

1. The heart in OI

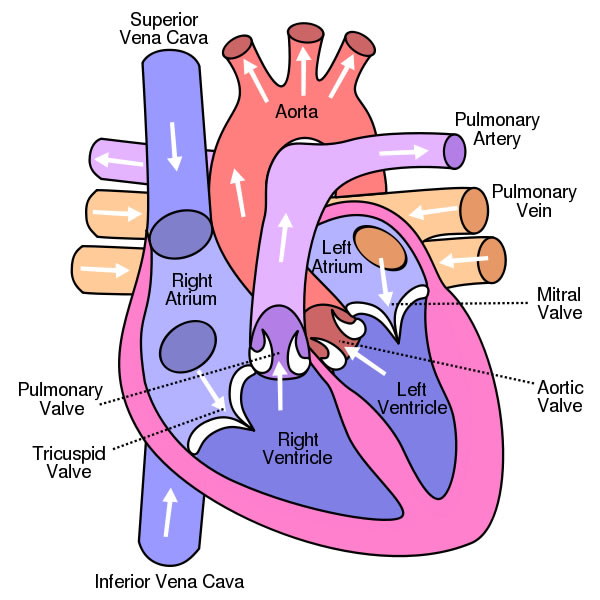

The cardiovascular system is made up of the heart and blood vessels. The heart is a muscle that works like a pump: it sucks in and propels blood and circulates it through the blood vessels throughout the body to supply nutrients and oxygen to the different organs. The heart (Figure 1) has 4 chambers or cavities: the two that receive blood are called the atria (right atrium and left atrium) and the two that propel blood are called the ventricles (right ventricle and left ventricle). It also has 4 valves: the tricuspid valve separates the right atrium from the right ventricle; the mitral valve separates the left atrium from the left ventricle; the pulmonary valve is at the exit of the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery, and the aortic valve is at the exit of the left ventricle into the aorta. The valves open and close like gates: when they open, they allow blood to flow through them, and when they close, they prevent blood from flowing backwards. So blood flows in only one direction.

How does blood circulate? With each heartbeat, the heart propels a quantity of blood into the aorta artery, which branches off successively to reach the whole body. The blood, loaded with oxygen and nutrients, feeds the body's cells and returns to the heart through the veins (it enters the right atrium via the vena cava). From the right atrium it passes through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. The right ventricle propels the blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery and into the lungs where it is recharged with oxygen. The oxygenated blood returns to the heart via the pulmonary veins into the left atrium. From there it passes through the mitral valve into the left ventricle which will pump it back out to the body through the aortic valve and the aorta artery.

Type I collagen is one of the main components of connective tissue, and is present in cardiovascular structures such as the walls of the heart, valves and arteries. Collagen fibres in the heart and blood vessels help to maintain the tension and architecture of the walls so that they do not dilate or collapse. However, unlike at the skeletal level, cardiovascular abnormalities in patients with OI are rare.

The following are some of the findings that can be observed in patients with OI:

- One of the main heart problems in patients with OI is that some heart valves can leak. In this situation, the blood circulates in the correct direction through the valve, but when it closes it does not do so completely and allows some of the blood to flow backwards. This is what we call a valve insufficiency and depending on the valve we will speak of mitral insufficiency, aortic insufficiency, tricuspid insufficiency or pulmonary insufficiency. A mild degree of insufficiency is common even in a healthy population and has no clinical repercussions. But when there is a greater degree of insufficiency, more blood backs up and makes the heart work harder. The heart tries to adapt by getting bigger, but in the long run this is not good for the heart and can lead to what we call heart failure. In this situation the heart is not able to do its job and cannot pump the blood properly to reach the whole body. Symptoms may then appear such as tiredness at the slightest effort, shortness of breath (blood can accumulate in the lungs and make breathing difficult), palpitations, swelling of the legs (oedema), etc. In any case, most patients with OI who have valve insufficiency have a mild form of OI and have no symptoms or repercussions on the heart.

Sometimes what we call valve prolapse can be observed (usually with the mitral valve), in which the leaflets or membranes that form the valve "fall" towards the ventricle, acquiring a concave shape. Prolapse refers only to the shape of the valve and in itself does not cause any problems, but when the prolapse is very marked, the valve may stop closing properly and valve insufficiency may occur.

The aortic valve is made up of 3 leaflets or membranes, which when open allow blood to flow through and when closed prevent blood from flowing backwards. In a small percentage of the general population, this valve has only 2 leaflets and we call it a bicuspid aortic valve. The percentage of bicuspid aortic valves in the LAA may be slightly higher than in the general population. Having a bicuspid valve may not have any clinical repercussions, but it is easier that over the years this valve stops working properly: either because it does not close properly (valve insufficiency) or because it does not open the leaflets as well and makes it difficult for blood to flow out (valve stenosis).

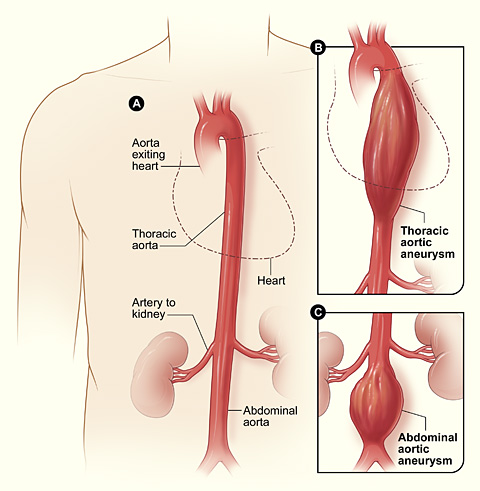

- As we have seen, the aortic artery is the main blood vessel leaving the heart to carry blood to the rest of the body. In some OI patients, it has been found to be somewhat enlarged (aortic dilatation) and can sometimes have a sac-like widening (aneurysm) (Figure 2). This is thought to be due to the alteration of collagen which makes the walls of the aorta weaker and with the continued passage of blood, it widens. Aortic dissection is a serious complication in which the wall of the aorta tears and allows blood to pass through it, which can lead to a rupture of the wall, with the consequent abundant loss of blood. Aortic dissection has been reported in patients with OI, but it is uncertain whether it occurs more frequently than in the general population.

- Finally, patients with OI may have the same cardiovascular problems as any other person: hypertension, cholesterol, angina and myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, etc., all of which are more frequent at an older age.

Treatment

Most of the cardiac abnormalities described above can be detected and monitored with echocardiography. Only occasionally will other tests such as catheterisation or MRI be necessary. In any case, most heart conditions in OI are mild and do not require any treatment or, at most, drugs to control blood pressure or diuretics to reduce the accumulation of fluids that occurs when the heart fails to perform its function perfectly. However, when the valvular or aortic involvement is severe, surgery is required to correct it. The timing of surgical correction and the surgical technique used must be individualised and agreed upon with the surgeon in charge, always taking into account the peculiarities related to the OI: greater difficulty in accessing the heart in the case of chest deformities or scoliosis, greater risk of bleeding, etc.